It looks like voter ID could be coming to California over the kicking-and-screaming objections of the people who are currently in power.

For anyone who believes elections in California are perfectly secure, consider this: It is legal in this state to walk into a county elections office up to seven days after the polls close carrying a Santa Claus sack filled with vote-by-mail ballots, none of them postmarked but all with the date of Election Day handwritten on the envelope, and the county is required to process those ballots.

A lot of ballots are floating around. Every active registered voter in California receives one in the mail automatically. For the Nov. 4 special election, that was a total of 23,093,274 ballots sent out statewide. Los Angeles County alone mailed out 5,844,744 ballots. Once they’re mailed, there’s no chain of custody, no records of how those ballots are handled or where. Ballots may be returned by mail, or to an official drop-box, or to an unofficial drop-box, or to any individual the voters allow to return the ballots for them.

In some states a Santa Claus sack of ballots might look like probable cause for an investigation, especially if it showed up seven days after the election. But not in California.

Here, state law says counties must accept ballots for seven days after the polls close, and the envelopes do not have to be postmarked at all. According to the California Code of Regulations, Title 2, Section 20991, it’s enough if “the voter has dated the vote-by-mail identification envelope or the envelope otherwise indicates that the ballot was executed on or before Election Day.”

What could possibly go wrong?

This is why it’s less than reassuring to many concerned California voters when government officials answer all questions about this process by mechanically repeating that there’s no evidence of fraud. California has changed the law in a way that enables ballot-box stuffing, while making it impossible to collect any evidence of ballot-box stuffing.

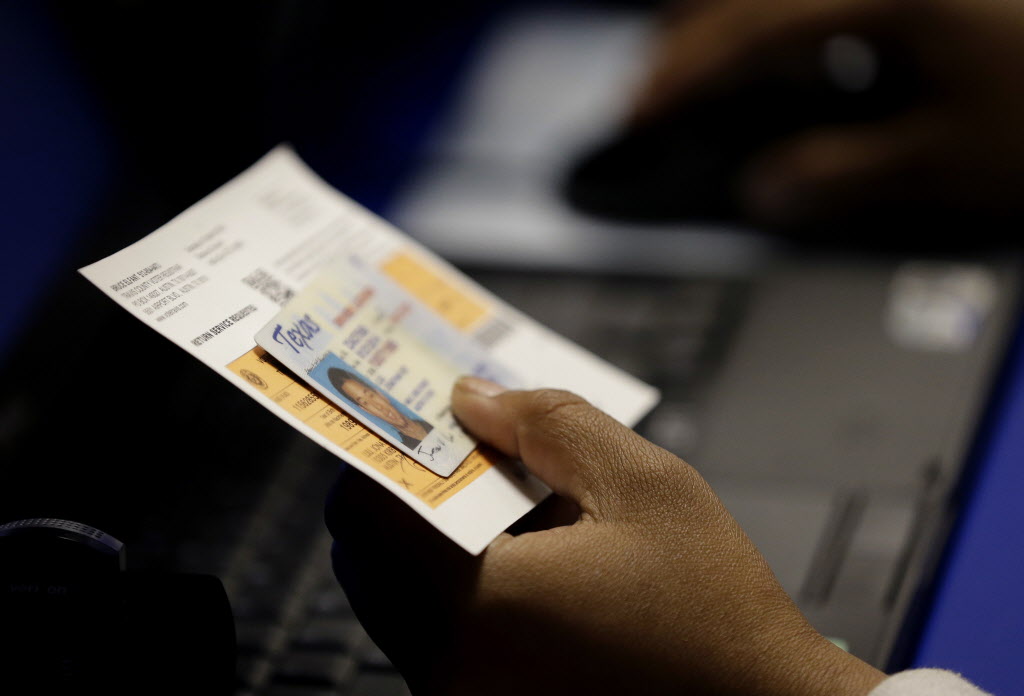

In March 2024, the voters of Huntington Beach decided they wanted what voters in 36 states already have, a voter ID law. They passed Measure A, which provided that starting in 2026, “The city may verify the eligibility of Electors by voter identification” in city elections.

The entire state government jumped up screeching as if it had seen a ghost. Attorney General Rob Bonta and Secretary of State Shirley Weber rushed to court to try to get Measure A invalidated. The Legislature quickly passed Senate Bill 1174, stating that no “local government” could “enact or enforce any charter provision, ordinance or regulation requiring a person to present identification for the purpose of voting or submitting a ballot at any polling place, vote center or other location where ballots are cast or submitted, unless required by state or federal law.”

The city government of Huntington Beach cited the “home rule” doctrine as authority for its voter ID law. Under the state constitution, charter cities (which have adopted their own local constitution) are “specifically authorized” to govern themselves “in matters deemed municipal affairs,” such as municipal elections. A lower court agreed, but last week, the California Court of Appeal for the Fourth Circuit ruled against Huntington Beach, striking down its voter ID law.

The court said voter identification is “a matter of ‘integrity of the electoral process,’ which our Supreme Court has held is a matter of statewide concern,” even in local elections.

Essentially, the appeals court said the state is in charge of election integrity, and if it chooses not to have any, the cities are stuck with that decision.

The purpose of voter ID is to match each ballot to an actual voter. For mail ballots, the voter typically writes a four-digit ID number on the ballot envelope. For in-person voting, the voter shows an ID before receiving a ballot. This prevents voter impersonation. Currently in California, there’s nothing to stop fraudsters from obtaining a list of registered voters, going to multiple vote centers, giving the poll workers someone else’s name and address and voting with that person’s ballot.

If that happens, there can be no evidence to prove it. Signatures in poll books are not examined or verified. And even if the real voter shows up later, he or she will be told “you already voted” and will have to cast a provisional ballot. Those are eventually verified, but only by checking to see if the voter is registered and if the voter already voted. All that’s verifiable is that somebody did. So the fraudster’s vote counts and the real voter’s vote doesn’t.

California is one of only 14 states that do not have a voter ID law. The others are New York, Illinois, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Vermont. The nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., also has no voter ID law.

Of the other 36 states, 24 require photo identification and 12 will accept a non-photo ID.

What would happen if California became the 37th state to adopt a voter ID law?

We may find out.

California voters have had the direct-democracy power of initiative since 1911. It allows voters to write and enact laws and constitutional amendments, going around the legislature and the governor. Now some Californians have written a voter ID constitutional amendment and are collecting signatures to place it on the November 2026 ballot. About a million signatures of registered voters are needed. Fox News reported that the leaders of Californians for Voter ID say they’ve already collected 500,000 signatures — in just one month — with polls showing 70% support for the measure.

If you’d like to read the initiative or sign the petition, it’s available at voteridca.org and voteridinitiative.com.

There’s more than one way to save democracy.

Write Susan@SusanShelley.com and follow her on X @Susan_Shelley