By the third hour in chains, Adan Caceres’ head was pounding and his lips were cracking from thirst.

Shackled at the wrists, ankles and waist, the Orange County wedding photographer sat pinned in his seat on a government plane, listening as the guards mocked the men around him as “criminals.” When one man begged to use the bathroom, he was refused, he said. So the stranger slid his shackled hands down, unzipped his pants and urinated into the same plastic water bottle he’d been given to drink from.

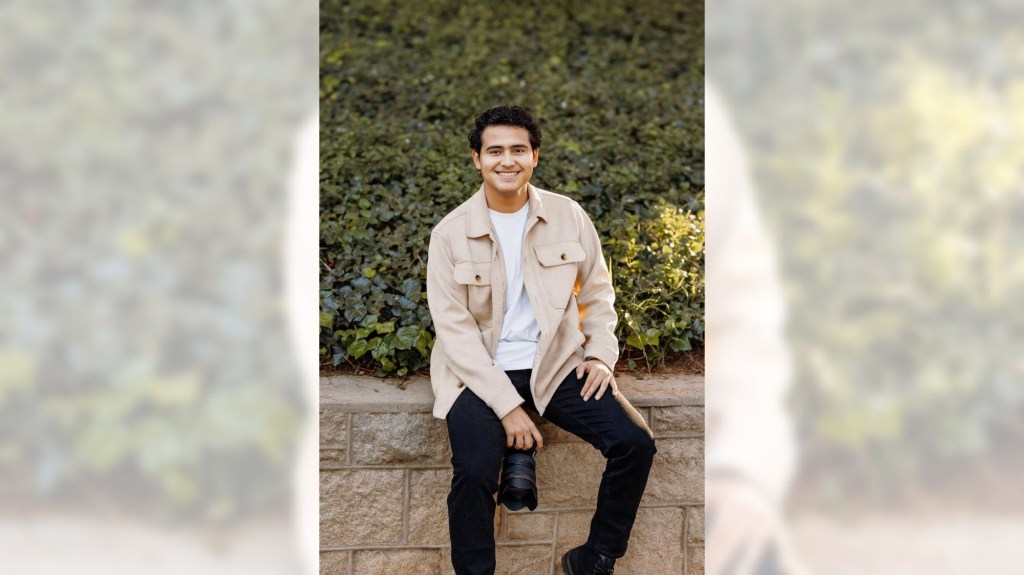

“I avoided drinking water because I didn’t want to have to go,” the 26-year-old said. “But then my head started hurting. We were dehydrated, the AC was off, people were fainting. It felt like we were dying in there.”

A week earlier, on Oct. 18, Caceres had been headed to Texas to photograph a wedding when he was detained while going through security at John Wayne Airport.

Caceres and his wife of a year and a half, who is a U.S. citizen, had been wary of travel as mass deportations increased nationwide under the Trump administration. Still, he had clients counting on him. And he believed he would be safe: Caceres said he had fled to the United States as a teenager seeking asylum and had continued following immigration requirements over the years, including completing biometrics and updating his address the previous year.

But his immigration case had grown complicated years earlier. In 2018, Caceres was issued a deportation order — something both he and the Department of Homeland Security confirmed. However, Caceres said he never received the order to appear in immigration court, as it was sent to an incorrect address, and he was not notified by the legal counsel he’d retained at the time.

Caceres’ current attorney filed a motion to stay his removal on Oct. 22, four days after he was detained, asking the immigration court to halt any deportation until the motion was decided. Caceres said he was deported days later without meeting a judge or being allowed to appeal.

DHS did not respond to a request for comment regarding the motion to stay the deportation.

Caceres said he was never advised of his rights throughout the eight days of his detention, and was misled into signing paperwork he was told was related to his belongings. He later learned it was an agreement barring him from reentering the United States for five to ten years, he said.

‘I’ll be fine’

Before he left for the airport that morning, he assured his wife that everything would be okay, and he would update her after he cleared security.

“I told her, ‘Babe, I’ll let you know when I’m inside of the airport. Don’t worry about it. I’ll be fine,’” he said in a telephone interview in November.

But while standing at the back of the security line, three masked men and one woman approached him, informed him he was being detained and seized his belongings.

“When she never heard the text from me,” he said, “I knew that she knew.”

His wife, who requested anonymity because of safety concerns, had driven him to the airport that morning. After kissing him goodbye, she waited until he disappeared into the terminal before heading home, unaware it was the last time she’d see her husband in person.

When no text came through, she checked his location to find that he was already at the ICE field office in Santa Ana.

It was just around the corner from the church where the couple first met. She rushed to Santa Ana and began knocking on the locked doors of unlit buildings still hours away from opening, hoping someone could help her. A landscaper working nearby eventually directed her to the right entrance.

Once she was inside, a worker handed her a sheet with information for an online detainee locator.

“I don’t know where my husband is, and they’re handing me a piece of paper,” she said. “I just felt so distraught. I didn’t know what to do.”

See also: ‘We may be deporting the wrong people’: New poll shows doubts about immigration crackdown

Immigration enforcement

Caceres is one of over 527,000 people who have been deported under the Trump administration as of November 2025, according to DHS. Despite claims the administration would go after “the worst of the worst,” data shared by DHS showed that 73.6% of people in ICE custody do not have a criminal record. A search for any criminal records for Adan Caceres in Orange or Los Angeles counties turned up nothing.

A survey released on Dec. 4 by Goodwin Simon Strategic Research, which the firm described as an “independent opinion research poll,” found that 7 out of 10 California voters believe a person should have “due process, including a judge reviewing their case to determine if they should be allowed to remain in the U.S.” – even if that individual has a criminal record.

Washington D.C. in particular has seen a sharp increase in the number of non-criminals detained. Within the first seven months of President Trump’s second term, ICE arrested around 150 people without a criminal record in the nation’s capital, the Washington Post reported. Between August 11 and mid-October, that number jumped up to 932 individuals.

In a press briefing in February, when asked how many people arrested by ICE had criminal records, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt responded, “All of them, because they illegally broke our nation’s laws, and, therefore, they are criminals, as far as this administration goes.”

Community Support

After she was introduced to her future husband at a church gathering, Caceres’ wife-to-be went around to other friends and members, asking what they knew of him.

“They said he was kind, a great friend, and would give you the last dollar in his wallet,” she said. “He truly, deeply, loves everyone.”

She also shared how uniquely forgiving her husband is, citing a conversation she’d had with Caceres about his early life in El Salvador. Her husband said that if he ever met the people who had killed his aunt, he would forgive them, she said, in hopes that it might change their path in life and lead them to God.

After Caceres was detained, his wife set up a GoFundMe in the hopes of raising $7,000 for legal fees to file a motion to appeal his pending deportation. Within days, they had raised $22,000, all donated by their church community, friends and family.

‘What’s going to happen?’

When Caceres arrived at the ICE field office in Santa Ana at around 5:30 a.m., about 30 minutes after being detained at the airport, he was placed alone in a cell.

“I was in my head for those three hours just thinking, ‘What’s going to happen? What am I going to do? What is my wife going to do? What happens if they deport me, where am I going to go?’” he recalled. “My whole family is in the States.”

When he was 10 years old, he exited his grandmother’s home in El Salvador early one morning to find the body of his 21-year-old aunt, he said. She had been stoned to death and her tongue cut out, according to Caceres.

By the time Caceres turned 11, he had been sexually assaulted twice, he said. Shortly afterwards, he and his brother began receiving threats from MS-13 members demanding they join the gang, according to Caceres. In 2014, the two boys decided to make their way to the U.S. in hopes of joining their mother, who had left the country when Caceres was 8.

“We literally just walked to the border of the U.S.,” he said. “We told them we are looking for our mom and we are looking for asylum because we are fleeing from our country. And so they took us in.”

After he turned 18, he moved out of the house he was living in with his mother and into a house with friends he’d made through his church. It was at that time he began honing his photography and building his career as a wedding and portrait photographer.

His career was thriving, until it came to an abrupt halt that Saturday morning.

Around six hours after arriving at the ICE field office in Santa Ana, Caceres was allowed to call his wife.

“All I said was, ‘Babe, call a lawyer. I love you. I’m really sorry. Don’t worry about me,’” he said.

More hours passed. At one point, two agents pulled him aside to take a photo of him, according to Caceres. From behind the camera, the two men smiled at him.

“That photo felt like one of those photos you see online of people that went fishing or that went hunting, and they captured a deer or a fish,” he said.

The agents offered no explanation for why the photo was taken.

Later that day, he was driven to the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, located about 85 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

Caceres explained that detainees are given what he described as prison clothes, in varying colors to signify their criminal statuses and corresponding danger levels. Caceres was in blue, designated for low-risk offenders or those with no criminal records, while detainees with criminal records receive either orange or red uniforms, indicating medium-risk or high-risk, respectively.

“They put you in a room with all of them,” he said. “I’m not gonna lie to you — it’s scary because you don’t know what the heck these people have done in their life.”

During the three days he was in Adelanto, Caceres said he suffered from sleep deprivation. Being in a room with unknown men of varying backgrounds didn’t lend to a restful environment, and detainees were continually disturbed throughout the day and night by staff checking identification bracelets.

“They just come and call your name out of nowhere and it’s like really loud,” he explained. “You’re barely getting three hours of sleep and then you’re up for the whole night because it sends you into panic mode of like, ‘Okay, where am I going? What’s going to happen? What’s next?’”

Many of the men tearfully shared their stories, mentioning wives, children and families they’d been separated from. Caceres said some suffered chronic health conditions and were not given their medication on time. Family members would arrive with medicine in hand, he said, but were turned away.

The online locator his wife was directed to was slow to update, she said, leading to days of confusion and uncertainty about where her husband actually was. After determining he was in Adelanto, she made plans to make the multiple-hour trip to visit him.

But on Thursday night, Caceres was already on a plane to El Paso. His wife was never notified.

“That’s when I knew I was getting deported for sure, because people in Adelanto told me once you’re sent to Texas, that’s when you’re going to be deported,” Caceres said.

The detainees were all shackled with handcuffs on their wrists and ankles, connected to another chain at their waist for the duration of the flights and layover.

“They treat you like you don’t feel anything,” Caceres said.

The discomfort grew as he and the other men were not allowed to stand or use the bathrooms. When detainees asked why, he said agents replied, “Well, you don’t have a right. We tell you what to do. And we don’t take orders from criminals.”

He saw men become sick from lack of medication. Some urinated in their pants.

After landing in El Paso, the group was kept in an un-air-conditioned bus for around four hours with no water or food, Caceres said.

“The people on the buses started moving to shake the bus to show them we needed help, we’re freaking dying in here,” he said.

The detention center, he said, was no improvement. Men were given aluminum blankets to fight the cold and told to use bathrooms that were covered in fecal matter and urine.

After that, they flew to Louisiana to pick up more men, then headed for El Salvador.

Caceres’ wife, again, was unaware her husband had been moved. Instead, she learned from a detainee, who was using an app called GettingOut, that he was no longer in the country. Even after he had landed in El Salvador, the locator still showed he was being held in El Paso.

DHS, in a Nov. 28 email, said that “Caceres will remain in ICE custody pending removal.” He had already been in El Salvador for over a month by then. DHS did not reply to questions addressing this apparent error.

“When we arrived, they started saying things like, ‘You’re free now. You don’t have to be afraid, you’re in your home country,’” Caceres said. “Nobody’s afraid of them — we’re afraid of what it’s like for our families left alone, our families unprovided for.”

An uncertain future

Once he set foot in the capital, San Salvador, he was given $5 for a taxi and the belongings that had been taken from him at the airport — except for his passport, which he said was kept by American officials.

His wife helped him arrange an Airbnb in the Salvadoran countryside, where he has been for the last month. He spends his days taking long walks and having long phone calls with his family and friends back home. He’s also been writing in a journal he bought on his third day back.

While he processed his imminent removal, Caceres said he thought of his photography clients who had already signed contracts and paid deposits for weddings into 2026. Most of all, he said, he worried for his wife.

“I’m not sure how my wife will be able to pay rent and pay all the bills by herself,” he said.

Back in Orange County, his wife is navigating daily life without him.

“It feels like I’m living a life that’s not mine,” she said. “I’m going to work, coming home, taking care of our dog, and it feels like I’m missing a piece of me. There’s an empty void.”

Caceres said his wife will be unable to visit in the near future, since she just started a job and cannot take extended time off — especially now that household expenses and legal bills fall on her. Additionally, Carceres mentioned that he worries for her safety in the country, even if she was able to visit soon.

She said they are waiting for confirmation on how long her husband may be banned from the U.S. Despite her new job, his wife said she will relocate if she and her husband need to start over somewhere else, though she clings to the hope that the U.S. can still be their home.

“I want to hold firm and believe that we can get him back,” she said.

For now, they connect through FaceTime calls and photos of their day-to-day lives.

“We are holding on to our foundation, which for us is God,” Caceres said. “Our commitment is to one another and God — not to our countries, not to our governments.”