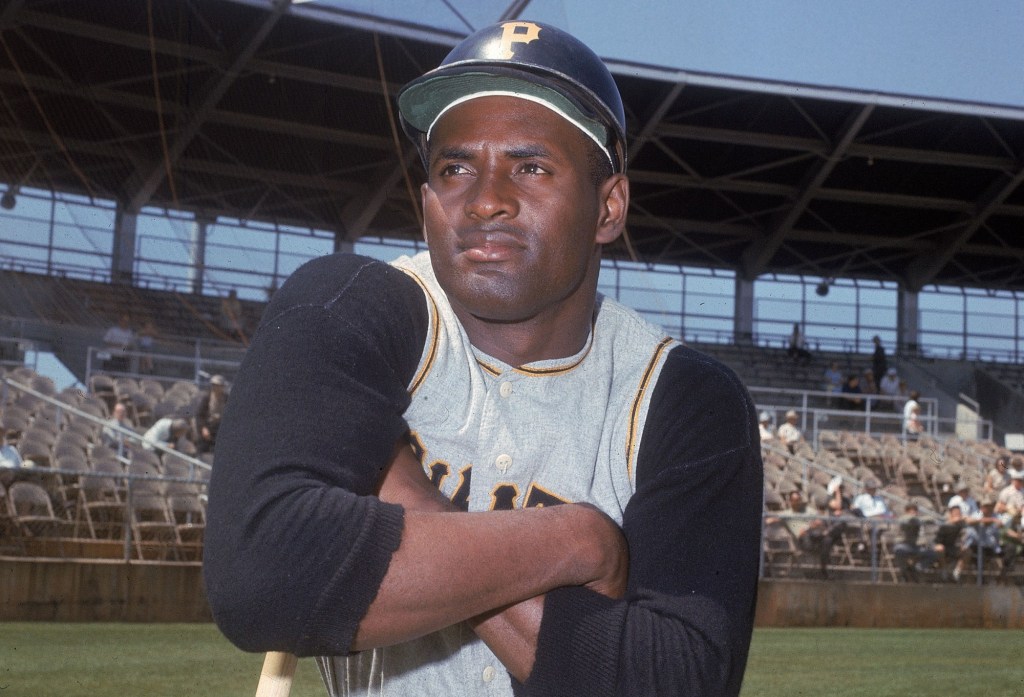

Anyone who ever had the opportunity to watch Roberto Clemente uncork a throw from right field – a laser, hard and accurate and in time to either throw out a foolhardy baserunner or keep him from trying to advance – instinctively understood what they were watching.

The Pittsburgh Pirates’ right fielder was poetry on the diamond, a five-tool player who helped his team to two World Series championships but amazingly was a bit underrated at the time. Consider this National League All-Star outfield of the 1960s: Clemente in right, Willie Mays in center and Henry Aaron in left.

Clemente was also a complex, fascinating man: proud to be Puerto Rican, sensitive to any hint of disrespect, and fully cognizant of what he considered his responsibility to help those who were less fortunate.

He recorded his 3,000th career hit on Sept. 30, 1972, a double against the New York Mets that made him the 11th player to reach 3,000. It turned out to be his last regular-season hit in a Hall of Fame career that included an MVP award (in 1966), four batting titles, 15 All-Star Games, 12 Gold Gloves and a World Series MVP in 1971.

And his life ended tragically just three months later, on a journey he had organized to fly supplies to Nicaragua after a massive 6.2 earthquake, when the plane he was in lost power and plunged into the Atlantic Ocean.

Nearly a half-century later, documentary writer-director David Altogge dug into the subject. The result was released this weekend: “Clemente,” a 101-minute film described in its media kit as “A powerful, joyful reminder that a life marked by passion, courage, and empathy can truly change the world.” (It’s being shown in Southern California at the Laemmle Monica Film Center in Santa Monica and the AMC Orange 30.)

“I did not grow up a baseball kid,” Altrogge said in a Zoom conversation this week. “I was terrible at sports … yeah, just really bad at sports.

“What drew me to this project was in 2018, I wrapped up a film and was just trying to think of what I wanted my next documentary to be about. … I wanted to do something that inspired people to do good, and reminded people that there is good in the world and that we as humans are capable of great good.”

He wasn’t totally oblivious to the story of Clemente, growing up as he did an hour outside of Pittsburgh, but he said he didn’t really dig into it until reading a biography of the player. He didn’t say, but that book might have been David Maraniss’ “Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero” (Simon & Schuster, 2007).

Altrogge said he “was just blown away. … I could certainly appreciate the artistry he demonstrated on the field, the mastery of the game. But I was particularly struck just by the way he lived his life for others and seeking out the marginalized in very quiet ways that were not publicized.”

Clemente’s sons, Roberto Jr., Luis Roberto and Roberto Enrique, are among the executive producers of the project, which took 6½ years to complete. I asked Roberto Jr., who was also on the Zoom call, what went through his mind during it all.

“People need to understand that every day of my life that I walk out the door … I have to talk about my father,” he said. “It’s something that I do every day of my life. I can be hiding in a corner (but) someone will find me that day. So it’s something that in many ways I’m used to.

“You know, every documentary hits some chords and some emotions. Obviously, this one does in many ways. So for me, once you see the finished product, you see how that needle threaded through that storyline and how impactful it is … (It’s) truly a blessing to see how people really are impacted by it.”

Said Altrogge: “Roberto is modest, but he’s very generous when he goes out. He and his brothers – I can’t imagine having to go out and not have the kind of privacy (with) people wanting to come up and talk about his father. I’ve seen Roberto and Luis Roberto … even their mother (Vera) on her last trip. We were very lucky that we got to film the last interview with her.

“And on our last trip here she was connecting with old friends, (former Pirate) Al Oliver and a gentleman named Luis Mayoral, who was a scout for the Pirates, and people were interrupting. … I’d be like, ‘Get out of here, I’m talking to my friends.’ Vera was just, just so gracious.”

It has now been more than a half century since the shocking news, on New Year’s Day 1973, of the tragedy that took Clemente’s life. But there are still strong emotions and strong memories, and Roberto Jr. credits his late mother, who passed away in 2019 at age 78, with carrying on his father’s legacy.

“I think that her, by her grace and how she touched so many people at the same time in her own way, really kind of helped cement that legacy the way it is, and the way it has grown for 50 years plus,” he said. “But I can tell you, that story in itself, what he did in 38 years, he lived in a flash. And we’re talking 53 years after his death. The story … he was an angel that touched so many people, still touching people.”

For the director, there was an almost overwhelming sense of responsibility to be true to the Clemente story.

“Not being Puerto Rican, and knowing that this is a Puerto Rican story, it was incredibly important to me to make sure that Roberto was able to say what he said in his life about Puerto Rico, and how he felt about being Puerto Rican, which was his primary identity,” Altrogge said.

“Before he was a baseball player, before he was a Pittsburgh Pirate, before he was anything he was Puerto Rican. So … I felt so honored that the Clemente family entrusted me with this story. I felt very underqualified in so many ways.”

And before we let this go, a reminder: Clemente could have spent his career as a Dodger.

Al Campanis, then a Brooklyn scout, saw him as an 18-year-old and filed a glowing scouting report. The Dodgers signed him in February 1954 for $5,000 and a $10,000 bonus, but the rules at the time stated that a player signing for a bonus of more than $6,000 had to stay on the major-league roster (as the Dodgers subsequently did with Sandy Koufax) or be subject to the Rule 5 draft.

Long story short: According to Maraniss’ biography, the Dodgers tried to hide Clemente at Triple-A Montréal, and that winter the Pirates – run by former Dodgers executive Branch Rickey – had the first Rule 5 pick and took him. Imagine the possibilities. And Buzzie Bavasi, then the Dodgers’ general manager, later suggested the Dodgers signed him for what they did primarily to keep him away from the San Francisco Giants, who offered $4,000 and an assignment to Single-A.

Altrogge noted that when word got out that this film was being made, lots of people contacted him with this story or that person to contact about Clemente. And Roberto Jr. noted that those stories brough out the emotions.

“Tears start flowing,” he said. “It is an amazing thing that when his name is mentioned, people react that way. It’s pretty amazing that it’s still happening after all these years.”

Baseball is obviously a huge component of this movie, and there’s plenty of footage of Clemente the Pirate, but Altrogge said his goal was to make this film accessible to non-baseball fans as well.

“Baseball is the backdrop, but this is the story of a humanitarian,” he said. “This is a human story.”

jalexander@scng.com