Baseball is hard, and it can be unforgiving even as excellence beckons. We don’t have to go back any further than Saturday night’s events in Baltimore to be reminded of that.

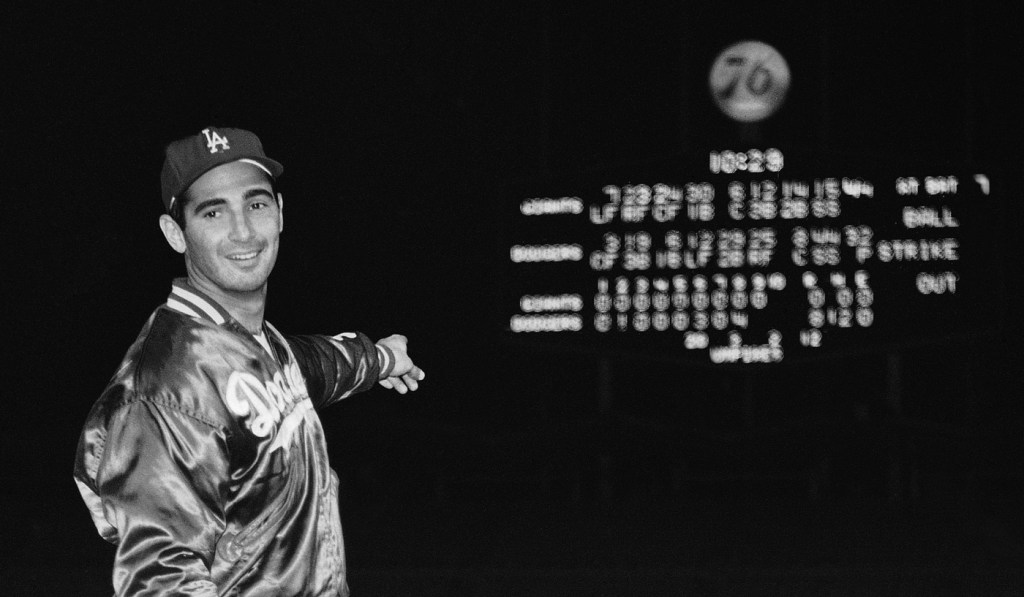

Greatness is rare. Perfection is rarer still. And the events of sixty years ago Tuesday – or, in the memorable voice of the late Vin Scully, “September the ninth, nineteen hundred and sixty-five” – represented a one of a kind moment in the game’s long history.

If you’re old enough to remember, reminisce with us. If you’re not, gather around as we recall the best combined pitching performance ever, and a description that was just as sublime.

That was the night Sandy Koufax pitched not only the fourth no-hitter of his career but what was then only the eighth perfect game in major league history, dating to 1880 – and the guy he faced, Bob Hendley of the Chicago Cubs, gave up only one hit that didn’t figure in the scoring in the Dodgers’ 1-0 victory. (Those Dodgers, a light-hitting team in a spacious stadium that was just 4 years old and hadn’t had the fences moved in yet, played a lot of such nailbiters.)

Scully’s play-by-play of that ninth inning, which remains embedded in the brain of any baseball fan of a certain age and is still accessible today via YouTube, was so literate – so perfect – that it was printed, verbatim, that winter in a tome called “The Fireside Book of Baseball,” and it read like a written narrative.

Worth noting: Those were the days when many baseball announcers honored the idea of a no-hit jinx and declined to acknowledge one in progress, especially one involving the home team picture. Scully never did so, figuring it was his job to report what was happening. And he didn’t jinx anybody. He called 26 no-hitters and three perfect games: Koufax in 1965, Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series, and Dennis Martinez for Montreal in 1991.

As Scully told me during a 2015 interview, “I think what happened, it was one of those rare nights, maybe the rarest of the rare. As Sandy was doing a perfecto, as the broadcaster, maybe that night I came as close to being perfect, you know? I mean, that doesn’t happen. It just doesn’t. … Some nights are a little better than others. And once in a while, you feel, ‘Gee, tonight it’s extra special.’ And that night, everything just fell into place.”

The Thursday game itself was a weirdly placed single game, maybe because it was Labor Day week. The Dodgers had lost in San Francisco on Monday and Tuesday to fall into a tie for the National League lead with the Giants – no divisions, kids, and the only postseason was the World Series. Wednesday, which was an off day, the Dodgers fell into a second-place tie with Cincinnati while the Giants won to take the league lead.

The Cubs had had Tuesday and Wednesday off after a series in Houston and were solidly ensconced in eighth place in a 10-team league, 15 games off of the lead. There was no sense that this was going to be anything special … but special always seems to sneak up on us, doesn’t it?

Koufax, in his 1966 as-told-to autobiography with Ed Linn, noted that it was “an odd bit of scheduling. It was hardly worth the trip.”

That night, backup Jeff Torborg was the catcher, rather than regular starter John Roseboro. And maybe this is a hint as to how unpredictable baseball can be:

“I was pitching, and I didn’t have any particular stuff at the beginning of the game,” Koufax said in the book. “Just average. I was throwing mostly curves through the early innings. In the last half of the game, though, my fastball really came alive, as good a fastball as I’d had all year.”

Hendley, a journeyman who was in his fifth season in the majors and went on to a 48-52 record in seven seasons, had been traded from the Giants to the Cubs earlier in the 1965 season. He was making his 22nd appearance and eighth start that season, and had just been recalled after spending August in Triple-A.

He, too, was perfect for the first four innings, but opened the fifth with a walk to Lou Johnson that turned into a classic 1960s Dodger rally: Sacrifice bunt by Ron Fairly, stolen base, throwing error by catcher Chris Krug for the run.

But there were extenuating circumstances. Krug said in a 2015 conversation that the ball was high, but “Johnson was sliding into third base and knocked Ronnie (Santo, the third baseman) down. Ron was on the ground when the ball went over the bag” and sailed into left field.

“The notoriety I’ve gotten for my error probably brought me more fame than if I’d thrown him out,” Krug said.

Johnson had the Dodgers’ only hit in the seventh, a two-out looper over Ernie Banks’ glove and down the right field line for a double. No one else reached base.

“Since we already had the run, I, needless to say, rooted for (Hendley) to get his no-hitter so we could walk into the record books hand in hand,” Koufax joked in the book, then added: “Like heck I did. I was sitting there rooting for us to score six more times and knock him out of the box.”

“I sympathized with him only as a fellow pitcher, only in retrospect, and – most of all – only when we were in the locker room with the game safely won.”

According to the Baseball Reference play-by-play, Hendley threw 77 pitches in his eight innings. Koufax threw 113 in nine. But no one really cared about pitch counts in that era, which could help explain why Koufax retired in the fall of ’66 at the age of 30, having pitched his last two seasons with an arthritic condition in a left elbow that Scully once remarked looked like a comma.

Koufax had thrown 98 pitches going into the ninth. Krug, who grew up in Riverside and was a rookie in ’65, was the first hitter and struck out on seven pitches, Sandy’s 12th strikeout of the night.

“I had a good at-bat,” Krug recalled. “It went to two strikes, one ball, and then went to 2-2. I fouled off a curveball, and then another pitch was a bit outside, so it (was) 3-2.

“The next pitch was a fastball. I can see it today. It was about that big (holding his hands apart), big as a balloon. I don’t know how I missed it. I swung and missed, and I figured I was a part of history.”

Koufax then struck out Joe Amalfitano, hitting for shortstop Don Kessinger, on an 0-and-2 fastball. Harvey Kuenn then was sent up to hit for Hendley, and as Scully told it, “I think Harvey said to Joey, ‘I’ll be right back.’”

He was, striking out on a 2-and-2 pitch to make history.

There have now been 321 individual no-hitters in the majors and Negro Leagues, according to Baseball Reference, plus 24 more combined no-hitters. There have been 16 perfect games in the 60 years since Koufax pitched his. And none of those other games finished with one combined hit. If you can find a better pitched game on both sides … well, good luck.

And one more footnote: Five days later, pitching at Wrigley Field before an announced 6,220, Hendley outdueled Koufax, 2-1. The next day the Dodgers lost again and fell to third place, 4½ games off the lead.

They proceeded to go on a 13-game winning streak, won the pennant on the next-to-last day of the season and defeated Minnesota in the World Series. with Koufax pitching Game 7 on two days of rest and shutting out the Twins, 2-0, without an effective curveball to earn Series MVP honors.

You think the current defending champs have such a winning streak in them as the stretch drive beckons? They might need it.

jalexander@scng.com

Originally Published: